|

Sabachthani |

||

|

Last update: 2016-03-20

Mobile

Friendly: m.messiahstudy.net

|

||

|

The Meaning Of Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?

A. Tradition. Commentaries say a lot about the mystery of Christ’s abandonment: God the Father laid the sins of mankind on his Son and forsake him (let him suffer hell) so that sinners can be saved and never be forsaken by God. I grew up with this viewpoint. Believers’ salvation will not be endangered if they continue to believe so. However, there is more embedded in it. B. Facts. Most expositors evade the difference between the cry of David and Jesus. In Ps. 22:1 and Matt. 27:46, the first part of the cry is the same (Eli, Eli, lama…); the last word differs. David said “lama azavthani” (why have you forsaken me?) and Jesus said “lama sabachthani” (why have you sacrificed me?). Both Matthew and Mark (in both Byzantine and Alexandrian texts) have Jesus saying sabachthani, not azavthani or shebakthani. In no way can we get rid of SABACHTHANI. The suffix “thani” means: you do this to me. Zabach is a well-known word in Hebrew Scripture. The NASB95 translates the word זבח (zabach) 295 times as sacrifice or offering, and the word עזב (azav) 170 times as forsaken, abandoned or leave. (Logos Bible Software 4, Guides, Bible Word Study. See Strong: H2076, H2077, and H5800). C. Questions. We are confronted by crucial questions:

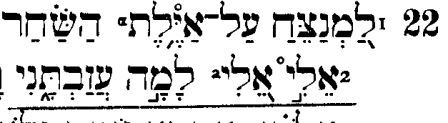

D. Hebrew Bible. The argument that Jesus spoke a rare form of Aramaic stands with weak legs on thin ice. The New Testament refers ten times to Hebrew but not to Aramaic. Alleging that “Eli” appears nowhere in the Hebrew Bible (except here), is incorrect, because Eli- was part of the names of 351 people in the Old Testament. The words “la” and “ma” both means “why” and occurs many times in Hebrew Scripture. “Eli, Eli, lama” are Hebrew words in the Hebrew Bible (Ps. 22:2). Check it out in this picture:

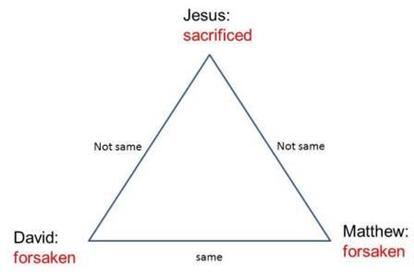

E. The problem. To understand the problem and the suggested solutions we have to look at the following diagram.

a. The word Jesus used (sabachthani or sacrificed) differs from the word David used (azavthani or forsaken) and from Matthew's translation (engkatelipes or forsaken). b. People try to solve the problem by changing Scripture. Luther changed sabachthani to azavthani. Today, many scholars change sabachthani to shebakthani (leave unharmed). Both changes of Scripture are unacceptable: it puts words into Jesus’ mouth. c. It is better to keep Greek Scripture unchanged, and to find an acceptable explanation for the differences. I think Matthew referred readers to Psalm 22 to let them see the difference between what David said and what Jesus said, and to make them think about the meaning of that difference. F. Shebak. The idea that Jesus used the Chaldean word “shebak” (שבק) and not the Hebrew word "zabach" (זבח) is widely advocated in an effort to bring Matthew's Hebrew and Greek words in line with each other. Many expositors avoid this topic entirely because they either think the two words are identical or they don't want to make a choice. There are convincing reasons why we should accept sabachthani and reject shebakthani. First, saying that Matthew transliterated wrongly, implies that the Spirit and the Bible made a mistake. Transliterate here means Matthew wrote Hebrew words in Greek letters. Second, Matthew’s transliteration for the Hebrew is σαβαχθανί (“sabachthani” with α as second and χ as fifth letter, not ε and κ as in “shebakthani.”). English does not have the guttural sound needed to pronounce the Greek χ and the Hebrew ח (they sound like the g in the Dutch "goede morgen"), so in English it is written as ch and pronounced as k. Third, the word “shebak” appears once in Ezra (6:7) and four times in Daniel (2:44, 4:15, 23, 26). Daniel 4 refers to the stump of a tree that was chopped down in the king’s dream. A voice said: “Leave the stump.” It did not mean forsake the stump, but leave it unharmed. Jesus definitely did not say, “Why have you left me unharmed?” In the well-known verse, "I will never LEAVE you nor forsake you" (Jos. 1:5), "shebak" is not used. It is also highly improbable that Jesus would start with Hebrew (Eli, Eli, lama...) and then borrow a foreign word from a foreign country. (See footnote: Aramaic words in the gospel of Mark). Fourth, if Jesus wanted to say he felt forsaken he could just have used the word David had (azavthani) without importing a foreign word (shebakthani). Jesus said what he wanted to say: lama sabachthani (why have you sacrificed me?) By doing that, he focused our attention on the essence of the Cross: an atoning sacrifice. The Chaldean word shebak leads to a marsh of questions about possible disunity in the Trinity. The first 3 and last 3 statements of Jesus from the cross refer indirectly to his atoning sacrifice; the 4th says clearly what he was doing. When Jesus cried out: “Why have you sacrificed me?” the answer is logical and biblical: God offered his Son as atoning sacrifice so that sinners can be forgiven and saved ‒ the essence of the well-known John 3:16. G. Unity of the Trinity. Shifting the focus from forsaken to sacrificed eliminates theorizing about God the Father abandoning God the Son, an act that is theologically inexplicable. Martin Luther asked, “God forsaken by God—who can fathom that?” We can view it this way: The Father turned his face away from Jesus, the Son of Man, laden with the sins of humanity, without forsaking the sinless Son of God, who was and remained part of the Trinity. There cannot be disunity in the Trinity. The Father's testimony about his Son, "This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased" (Matt. 3:17, 17:5), is eternally true, even on the Cross where he was completely obedient by finishing the Father's plan of salvation (Phil. 2:8-9). A few minutes after he cried "lama sabachthani," he gave his spirit over to the Father. They remained One (John 10:30). John Calvin remarked on Matt. 27:46 that Christ "felt himself to be in some measure estranged from him (God)." "The perception of God's estrangement from him, which Christ had, as suggested by natural feeling, did not hinder him from continuing to be assured by faith that God was reconciled to him." "By the shield of faith he courageously expels that appearance of forsaking." John M. Gibson (The Expositor's Bible) comments, "There is no reason indeed to suppose that the Sufferer was really forsaken by God, even for a moment. Never was the love of the Father deeper and stronger than when His Son was offering up the all-atoning sacrifice. Never was the repeated testimony more sure than now: 'This is My Beloved Son, in Whom I am well pleased.' But none the less was there the sense of forsakenness." William Hendriksen held this opinion on Matthew 27:46 -- "The question has been asked, 'But how could God forsake God?' The answer must be that God the Father deserted his Son's human nature, and even this in a limited, though very real and agonizing, sense. The meaning cannot be that there was ever a time when God the Father stopped loving his Son. Nor can it mean that the Son ever rejected the Father. Far from it. He kept on calling him "My God, my God." And for that very reason we may be sure that the Father loved him as much as ever." H. Sacrifices. The Old and New Testaments often refer to vicarious sacrifices. The idea of the Messiah as the sacrificial Lamb of God runs through the Bible. All the animal sacrifices pointed to him (Heb. 9:12-14). Abraham said to Isaac, “God will provide for Himself a Lamb.” Isaiah prophesied, “He was led as a lamb to the slaughter” (Is. 53:7). John the Baptist announced him as “The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29, 36). The apostle Paul said, “Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed” (1 Cor. 5:7, NIV). The apostle Peter confirms, “You were not redeemed with corruptible things, like silver or gold… but with the precious blood of Christ, as of a lamb without blemish” (1 Pet. 1:18-19). In a vision of heaven, the apostle John saw “a Lamb as though it had been slain,” and multitudes of angels sang, “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain” (Rev. 5:6, 12, see 7: 14). The NT refers at least 18 times to salvation through the blood of Christ. However, the apostles did not refer in their letters to Christ's forsakenness. I. Omissions.

One

does not find references to the forsakenness of Christ where it is to be

expected. Jesus warned his disciples three times about his coming death

without mentioning abandonment by his Father. To the contrary, he stated

twice that his Father had not left him because he did his will (John 8:29,

16:32). The record about Jesus' struggle in Gethsemane does not refer to the

dread of being forsaken by the Father. Some preachers assume this was the

cause of his fear, but this assumption is not supported by scripture. The

letters of the Apostles do not link atonement and reconciliation to the

forsakenness of Christ. Check these: J. "Forsaken" in NT The New Testament uses many different words to indicate forsaken/abandon. The word Matthew used (engkatelipes) is used 8 more times in the New Testament: all (except the first two) with reference to people, not Christ (Acts 2:27 and 31, Rom. 9:29, 2 Cor. 4:9, 2 Tim. 4:10 and 16, Heb. 10:25, 13:5). On the day of Pentecost, Peter emphasized that Christ was NOT abandoned to the grave or in hell (eis hades, Acts 2:31). He suffered hell on the cross before his death. Referring to the cross, Jesus said the Father have not left him because he always does his will (John 8:28-29). The Greek word kataleipo (forsake, abandon, leave) is used in various forms 24 times in the New Testament, without referring to Christ on the Cross. In first century theology, not the forsakenness but the sacrifice of Christ was front and center. Emphasis on his abandonment came later. K. "This is" (Matthew) Despite all the evidence from Hebrew and Greek Scripture, some maintain that Matthew used the words THIS IS between his Hebrew and Greek phrase, assuming that the first equals the second: "Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?" this is "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" Like German, Greek has male, female, and neutral words. So the word for THIS can be either houtos or haute or touto. In this case, Matthew used the latter (touto). There are several places in the gospels where "this is" does not mean two things are equal, but one resembles the other. Likewise, a flag resembles a country, but is not the country.

Therefore, "this is" in Matt. 27:46 can be interpreted this way: "Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?" this is like (resembles) "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" Jesus as the Word of God reinterpreted David's cry. When David felt forsaken, God had a higher purpose in mind. When Jesus looked forsaken, God's purpose was to give him as atoning sacrifice so that sinners can be saved. L. "This is translated" (Mark) Mark used the word methermeneuomenon (derived from hermeneuo) between his "Aramaic" and Greek quotations of Jesus’ fourth saying on the cross (Mark 15:34).

Does it matter whether one interprets sabachthani as forsaken or as sacrificed? The phrase, "Why have you sacrificed me?" avoids the escape route of explaining Jesus’ vital question by means of rare Aramaic words. It keeps us tied to Hebrew Scripture, and at the same time gives a deeper meaning to an Old Testament prophecy. It also changes the nature of Christ’s cry. It is not the complaint of a desperate victim, David, but the shout of our victorious Savior, Jesus. When Christ asks with a loud voice, “Why have you sacrificed me?” he wants all believers to shout, “To reconcile us with God, and to give us eternal life! Hallelujah!” ~~~~~ Footnote on Aramaic words in the gospel of Mark. Theological introductions to the gospel of Mark are fraught with uncertainties. Different theories exist about its author, sources, place of origin, original form (Greek or Aramaic), goals, readers, style, and date of completion. In the end, no sure conclusions are made. The same vague explanations are submitted for the so-called Aramaic words used by Mark: Boanerges (3:17), Talitha koum (5:41), Ephphatha (7:34), Abba (14:36), Golgotha (15:22), and Eloi Eloi lama sabachthani (15:34). Mark's transliteration (writing Aramaic words with Greek letters) does not fit in easily with real Aramaic. The theories remain in suspense. (The word "corban" (7:11) is a Hebrew word (קרבן) that is used 79 times in the Old Testament. If Mark used a Hebrew word in one place, he could have done it in another too). Then there are also the Bar-names (instead of the Hebrew "Ben:" son of): Bartholomew (3:18), Bartimaeus (10:46), and Barabbas (15:7). These names show that Aramaic could have been used in Israel in the first century. The fact that two of the disciples and the first seven deacons had Greek names (Acts 6:5) does not prove all Israel spoke Greek at that time. It is highly likely that the Hebrew language did not completely die out during the exile but was revived when many returned to their homeland -- as they did in 1948. Even today, when expatriates return to their country of origin, they like to speak the native tongue. Daniel and Ezekiel wrote their books in Hebrew during the exile, except for those parts where Daniel and the Babylonian king had a conversation in the king's language. It is not surprising that the phrase, "Eloi Eloi lama sabachthani," does not occur like that in the Aramaic New Testament. The commentators have to stretch and shrink it to make it fit. The phrase Jacob used in Gen. 33:20 ("El Elohe Israel," God, God of Israel) was repeated by Jews for centuries. Mark's Eloi may be a transliteration of Elohe. Because of the uncertainties concerning Aramaic words in Mark's gospel, I focused on Matthew's record in which "Eli Eli lama" corresponds with the Hebrew of Psalm 22. And if the first three words are Hebrew, I am quite sure that Jesus would have followed it up with another well-known Hebrew word in the Bible, namely zabach (sacrifice). ~~~~~~

NOW AVAILABLE The baker of Capernaum meets the carpenter of Nazareth.

|